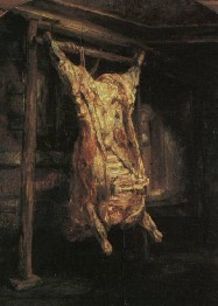

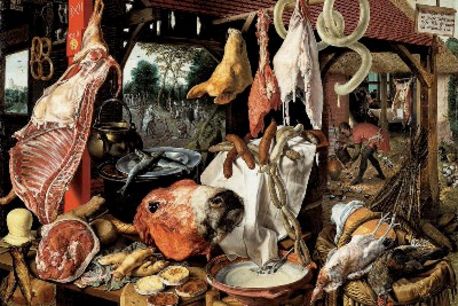

There was little reference to the fatted calf in art or literature in the centuries following the New Testament. This is not so surprising considering how little interest humanity showed in culinary delights during the darkness of the Middle Ages. One of very few canvasses depicting a calf, is the sixteenth-century painting by Pieter Aertsen in which he portrays a carcass in juxtaposition to the luxurious foods of his day, with beggars in the background. In between the hams, pies, butter, sausages and poultry, he has painted the head of a fatted calf, prominently positioned in the foreground. Rembrandt also painted a fatted calf, hoisted in a butcher shop.

A banquet laden with fine delicacies was the invention of France’s Sun King, Louis XIV. These were curious times, rife with debauchery: times when chefs were happy to serve stuffed peacocks and stuffed swans, still dressed in their feathery coats. François Vatel was one of the first of these chefs, who committed suicide in 1671 in the castle at Chantilly during a banquet that his boss, the Prince of Condé, was holding in honour of the Sun King. His reason: the fish had not been delivered to the kitchen in time.

Gastronomy only became fashionable in the eighteenth century, and even then, only for the likes of kings, tsars, dukes and the nouveau riche: anyone who could buy themselves their own chef.

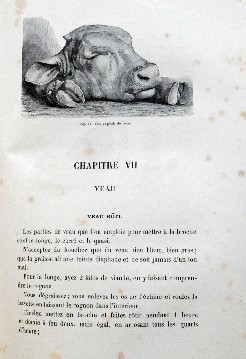

This was the setting in which Jules Gouffé grew up, a student of the renowned chef Antonin Carême and the first person to go into detail about the uses of the fatted calf, in his book Le Livre de Cuisine no less, published in 1867 in a variety of languages. Gouffé dedicated a generous number of pages to veal, and was probably the first to mention glace de viande. For the recipe, he used 3kg sous-noix de veau, 3kg veal shanks and 3kg breast of beef. He took the meat from the liquid and used it for le grande bouillon; adding that he had learned this technique from M. Crouhat, the chef at Rosny, the castle of the Duchess of Berry. Gouffé’s inclusions about veal generally read something like this: “Accept veal from a butcher only when it is white and fat, and when the fat is transparent, not matte.” This nineteenth-century chef’s favourites were Veau Rôti, Blanquette de veau and Veau à la bourgeoise, and since we are working our way to the heart of French cuisine, we have included the recipe.

Veau à la bourgeoise

The round fillet and leg are the best choice here. Cover the meat with fatty bacon and put it in a 5-litre pan. Add 2 litres of bouillon and a calf’s foot. Bring to a boil and then add carrot, onion, clove, a double bouquet garni, salt and pepper, and simmer over low heat for 3 hours with the lid three quarters on the pan. Cover the meat with a very hot lid to give it some colour, ladle the liquid over the meat 5 or 6 times and use a needle to see if it is cooked. Put the mean on a platter. Use a sieve to strain the jus, deglaze and reduce by half. Add a teaspoon of caramel for colour. Slice the carrots in equal pieces and remove the butcher’s twine from the meat. Garnish the platter with glazed onions and cover with jus. Save the rest of the jus for tomorrow.

Auguste Escoffier was another chef from this period, who also gained fame with a book, Ma Cuisine. He had been Jules Gouffé’s student and did little more than copy his master’s recipes, and add a few of his own for good measure. Ma Cuisine, later published in a number of languages, is still viewed as the foundations of gastronomy. Almost all chefs are likely to have a copy. In fact, credit really should go to Escoffier for his achievements in introducing French cooking to a wider audience. One could call it lucky timing, as more and more people at the beginning of the twentieth century were able to read, but they were also starting to learn how to cook, at home, and in response to the emergence of the cookery book. Books were published in their hundreds; some with recipes for veal. This was a trend that filtered its way throughout Europe, putting veal firmly on the menu.

Having reached the first half of the twentieth century, it might be interesting to look at what the fatted calf looks like now. In the Larousse Illustré, the leading French encyclopedia of the time, Larousse says: “The colour of veal varies, depending on food and age, from white to rosé to red. The best quality comes from a two to three month old calf that was fed with milk. Refuse the meat of a gosselin, a calf killed for its skin when it is only 8 to 21 days old. Its meat will be yellowish and lacking in nutritional value, its fat soapy and sticky to the touch.” In a handbook for butchers dating from 1936, we read: “A calf that is destined for fattening straight after birth, will be fed nothing but whole milk, and depending on the region, a few eggs. The soft, cheap meat from newborn calves can be used as the basic ingredient for sausages, or for making stock.”

Its role as a symbol of celebration and its status among the wealthy up until now, has kept the consumption of veal and the slaughter of calves to a minimum. At this point in time, farmers were caring for their calves, sometimes to order, and feeding them milk and eggs, which were expensive products. However, the world is about to change; mainly due to the discovery of formula milk in the post-war period.